He arrived at the Nyagoe competition as the outsider, the American who had trained alone, watched clips online, and wondered how he would be received. But as soon as he stepped onto the grounds, any worry about belonging faded. Strangers walked up to offer rope, water, and help.

By the time the clock neared 2 pm and the whistle was about to blow, he no longer felt foreign. What followed, though, tested him in ways he did not expect.

Brandon Jackson’s day had started hours earlier in a completely different world. He woke up at 6 am and spent the entire morning reviewing for what he considered his toughest class. The three-hour exam ended around 11 am, leaving him drained but relieved. After a quick meal back at his hostel, rice, a bit of dal, and some water, he met friends who agreed to accompany him to the competition. They reached the grounds at 1 pm in the afternoon.

He was excited as he walked in, scanning for the coordinator and searching for the implements he had seen online. Without warming up, he walked over while a crowd of about thirty watched. He lifted the log to his shoulder with ease. People looked around, wondering who he was, and the Nyagoe TV host noticed him immediately. After a brief conversation, he wrote down his information, received a quick briefing on the rules, and began to warm up.

Soon, it was his turn. He bowed to the Dzongda, spoke with the TV host, and prepared for the whistle. The moment it blew, the world went silent. He heard nothing, not the host, not the spectators, not even his friends, who later told him they had been shouting as loudly as they could. His mind was entirely fixed on the course ahead.

The log drag was the part he feared most. The friction of the grass could make or break the attempt, and he had no idea how difficult it would feel. Bracing himself for a heavy pull, he began.

To his surprise, the drag felt light. He ran with it, finishing the first 50 meters without any strain. When the time came to lift the log onto his shoulder again, he felt confident. He had practiced countless times and knew that logs required more technique than pure strength. He picked it up easily, but this time, the fatigue set in during the carry. His breathing felt fine, but his legs, especially his upper quads, were growing weak.

At the end of the carry, he was advised to take rest, but because he felt steady in his breathing, he decided not to stop. He moved straight to the over 100 kg heavy sandbag. He brought it to his chest, but his legs wobbled, and it slipped. He still believed he could move fast, so he rested only about ten seconds before trying again. It fell a second time, and now the exhaustion in his legs was undeniable.

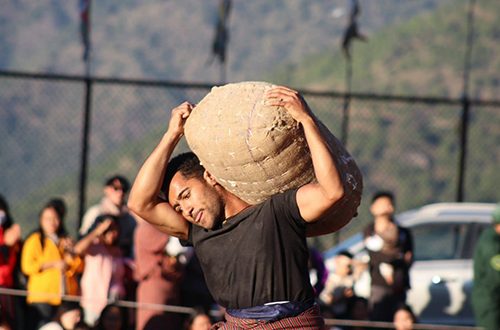

This moment mattered. Failing twice meant he had only one more chance. After taking a longer rest, about forty seconds, he approached the sandbag again. This time it felt weightless. He lifted it quickly, just as he did in training. His legs were still trembling, but he placed the weight in the perfect position before tossing it onto his shoulder. It nearly slipped off, but he caught it just in time.

People were shouting loudly, and the coordinator’s voice broke through the silence that had surrounded him since the start. With the sandbag on his shoulder, he let out a deep breath. He knew then that he would be able to finish the rest.

The carry was slow and careful. The ground was uneven, and he knew that if he dropped the weight accidentally, he might not be able to pick it up again. He walked steadily until the end, then prepared for the final event, the tyres lift. The lift was usually easy for him, but this time, his legs shook beneath him. He managed to raise it without trouble, though he stumbled slightly at the top.

When the event ended, everything felt immediate. The host asked him questions while he was still catching his breath. His legs were shaking, and he struggled to focus. Soon after, all the competitors gathered for the awards. Standing in line, he could understand about 30 to 40 percent of the Dzongkha if he really concentrated, but he was so exhausted that he could barely remain upright. His legs kept trembling beneath him, though it wasn’t visible on camera. The contrast between the formal award ceremony and the physical strain he was feeling struck him as unintentionally funny.

What remained clear throughout the experience was the support around him. Whether it was BBS staff, other Nyagoes, or spectators, everyone helped in small ways, fetching rope, offering water, or guiding him through what to expect. The warmth surprised him. He had worried he would be left figuring everything out on his own, but people stepped in at every step.

Now that the competition is behind him, he feels he finally understands what the equipment truly feels like, the sandbag, the log, the tyres, the grass, the pacing, the accumulated fatigue. He knows exactly where he lost time and where his weaknesses showed. And with that clarity, he has already begun training again, preparing for next year.

The Bhutanese Leading the way.

The Bhutanese Leading the way.