According to the research, in urban areas, testing of 13,640 water samples for E. coli, which signals fecal contamination, showed that only 52.8 percent met the national safety standard of zero bacteria per 100 milliliters

A recent study published by the Royal Centre for Disease Control (RCDC) has revealed that while access to clean and safe water is crucial for public health, ensuring its safety remains a persistent challenge in Bhutan.

The research, which was conducted between 2017 and 2024, analyzed over 35,000 water samples from urban and rural areas, drawing data from the Water Quality Monitoring Information System (WQMIS).

Urban areas included 31 health centers across 19 dzongkhags, with 20,982 samples, while rural areas included 242 health centers and 14,361 samples across 20 dzongkhags. The study compared results against the Bhutan Drinking Water Quality Standards (BDWQS) and World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

The report states, “The impacts of climate change, such as unpredictable weather patterns and drying of water sources, further affect the availability and reliability of water supplies.”

It found that rapid urbanization and development are also putting growing pressure on water resources, affecting both quality and quantity.

Globally, 2.2 billion people lack safely managed drinking water, and contaminated water remains a leading cause of diarrheal diseases, cholera, typhoid, and other infections, resulting in over 500,000 deaths annually, nearly half of them children under five.

Microbial contamination, identified as the most critical concern, refers to harmful bacteria, viruses, or other germs in water. These microbes, often from human or animal waste, can cause illnesses such as diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and, in severe cases, life-threatening infections.

In the study, Escherichia coli (E. coli) was used as a key indicator. E. coli is a type of bacteria normally found in the intestines of humans and animals. Its presence in drinking water shows that the water is contaminated with fecal matter and may contain other disease-causing germs.

Both urban and rural areas in Bhutan face significant challenges in water safety.

According to the research, in urban areas, testing of 13,640 water samples for E. coli, which signals fecal contamination, showed that only 52.8 percent met the national safety standard of zero bacteria per 100 milliliters. This level of contamination means that a significant portion of Bhutan’s urban population could be consuming water that carries harmful pathogens.

The report states, “The most critical concern identified was the consistently poor microbial quality of drinking water. On average, only 52.8 percent of samples complied with the Bhutan BDWQS for microbial contamination.”

This poor microbial quality highlights that fecal contamination is widespread in Bhutan’s drinking water systems. Since the Bhutan Drinking Water Quality Standard (BDWQS) requires zero E. coli per 100 milliliters, the research shows that only about half of the samples met this benchmark, which means that many households are regularly consuming water that may carry harmful pathogens.

Unsafe microbial quality is directly linked to illnesses that can spread quickly in communities, especially affecting children, the elderly, and people with weakened immunity.

The persistence of contamination despite monitoring efforts shows that current treatment and distribution systems are not adequately protecting public health.

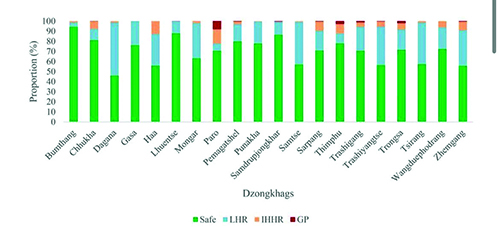

Moreover, eight dzongkhags, including Trashiyangtse, Trashigang, Lhuentse, Samdrupjongkhar, Mongar, Punakha, Wangduephodrang, and Zhemgang, had compliance below 50 percent only. Residents in these districts are, therefore, at high risk of waterborne diseases, especially during the rainy season (May to September), when runoff and contamination from water sources increase.

Water clarity, or turbidity, also revealed hidden risks. While 95.2 percent of urban samples met Bhutan’s national standard, only 67.3 percent met the stricter WHO guideline, indicating that water can appear clean yet still carry harmful germs.

Clear water is important because when water is cloudy, the dirt and particles can hide germs and make it harder for treatment, like chlorine, to kill them.

The highest turbidity in urban areas was recorded in July, showing how monsoon rains increase contamination.

Moreover, residual chlorine, which is needed to keep water safe as it travels through pipes, was found in only 11.9 percent of treated urban samples. This means most of the water reaching households had little to no lasting protection against germs.

Without enough chlorine, any bacteria entering the system through leaks, damaged pipes, or storage tanks can survive and spread. Issues such as under-dosing, ageing pipelines, and treatment plants located far from settlements make it even harder to maintain safe levels, leaving people at higher risk of waterborne diseases.

The study’s data send a clear warning that urban residents are constantly exposed to contaminated water.

In rural areas, the study found that 70.1 percent of rural water samples met the national standard of zero bacteria per 100 milliliters, with Dagana falling below 50 percent, indicating high risk.

The research shows that in rural areas, microbial safety drops significantly during the monsoon season (May to September). During the dry season, 73.8 percent of samples were classified as safe, while during the rainy season, this fell to 66.5 percent.

Correspondingly, low, medium, and high-risk water increased, demonstrating that seasonal rainfall directly increases the risk of contamination.

Water clarity also raises concern, in which 87.9 percent of rural samples met the national turbidity standard, but only 44.7 percent met the stricter WHO guideline.

The research notes that Bhutan continues to face challenges in ensuring safe drinking water, with microbial contamination identified as the most critical issue. Only 52.8 percent of urban and 70.1 percent of rural samples met national microbial standards, with compliance dropping during the monsoon season.

Low residual chlorine levels and high turbidity in some areas further compromise water safety. The study emphasizes that targeted improvements, such as upgrading treatment facilities, ensuring consistent disinfection, standardizing microbial testing, and implementing Water Safety Plans (WSPs), are essential to achieve Bhutan’s Five-Year Plan goal of 90 percent safely managed drinking water and progress toward SDG 6.

The Bhutanese Leading the way.

The Bhutanese Leading the way.